Few painters have rewritten a country’s visual DNA as radically as Martiros Saryan (1880-1972). In the decade before World War I he abandoned Impressionist greys for blazing, near-flat fields of colour that looked more like illuminated manuscripts than plein-air studies. Those chromatic experiments—later codified on everything from Soviet postage stamps to twenty-first-century tourism billboards—proved that a palette can serve as a nation-building toolkit.

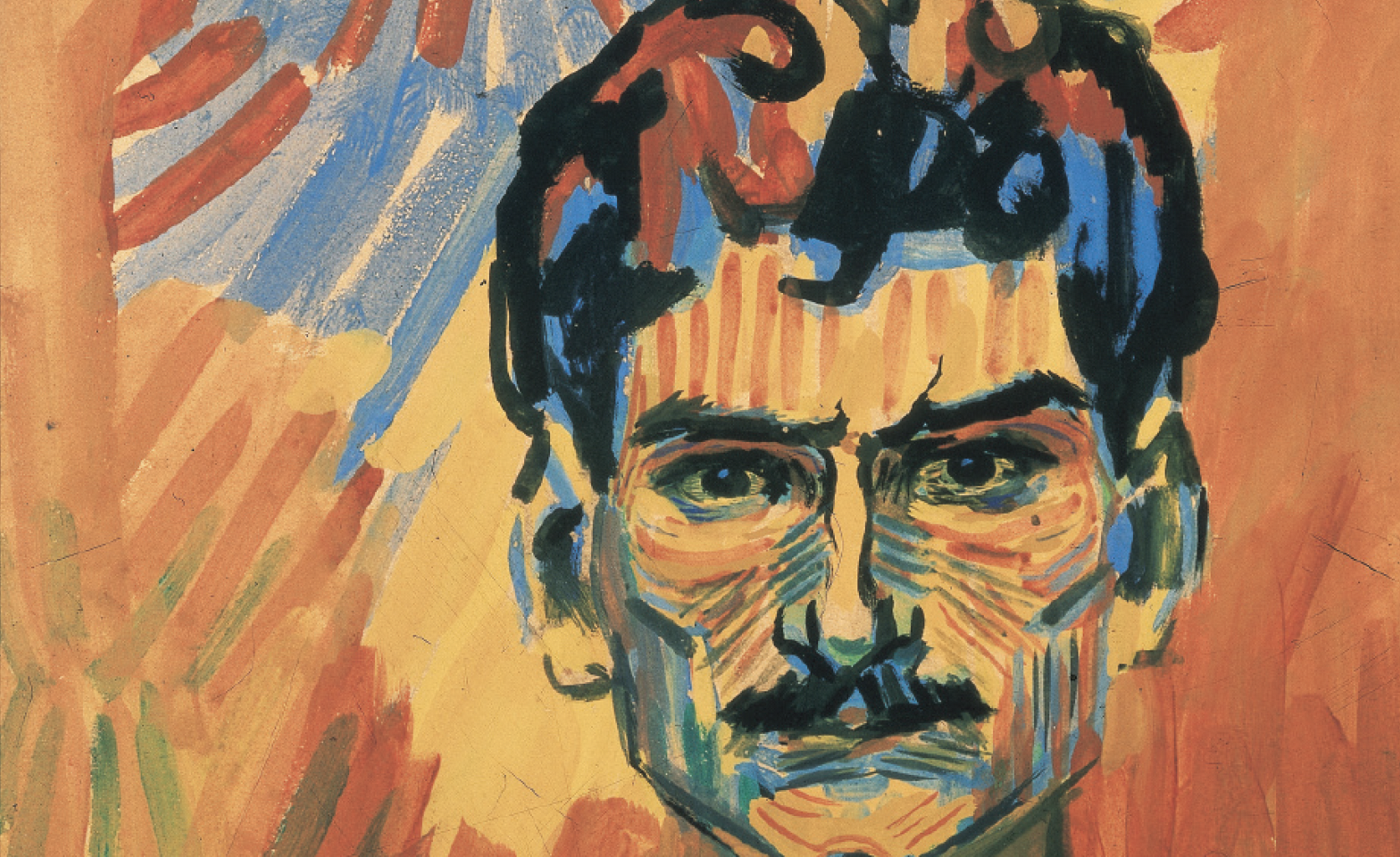

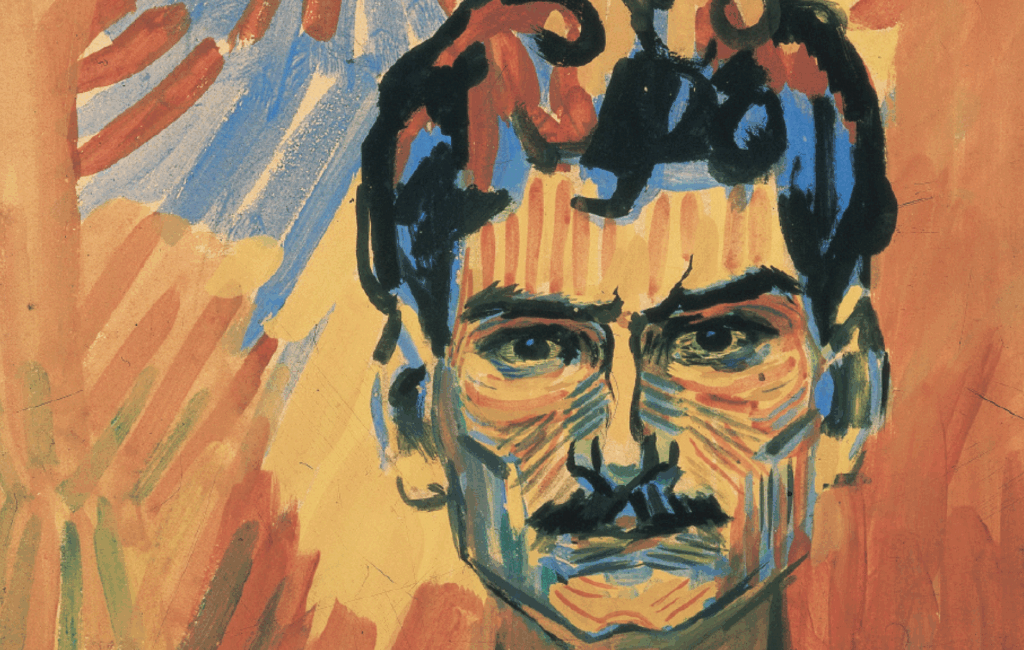

Born in Nakhichevan-on-Don and trained at the Moscow School of Painting, Saryan devoured Puvis de Chavannes, Gauguin and the “Blue Rose” Symbolists, yet kept one eye on Armenian carpet dyes and medieval miniatures. By 1905 he had switched from oil to tempera, a medium that “electrified the colours in his palette,” preparing the ground for an indigenous Fauvism years before he encountered Matisse.

The breakthrough came with Pomegranate Tree (1907) and By the Sea – Sphinx (1908). In both, outlines are pared to essentials while reds, cobalt blues and yellows clash like enamel in a khachkar. Critics noted the absence of atmospheric depth, yet that very flatness—echoing carpet design—let Saryan treat landscape as a portable icon: a nation could be rolled up, shipped abroad, and unfurled on any salon wall.

Between 1910 and 1913 the artist roamed Turkey, Egypt and Iran, refining what he called his “oriental cycle.” Constantinople Dogs (1910) wilts beneath a lapis sky while Date Palm (1911) stages camel, earth and canopy in three stacked colour blocks. Space rises, miniature-style, “from the bottom to the top,” refusing European perspective and thus re-anchoring vision in the East.

Genocide and exile scattered compatriots in 1915, but Saryan decided to do the opposite: he repatriated. Settling permanently in Yerevan in 1921, he began cycling through motifs of Mount Aragats and Mount Ararat, sculpting form “by eliminating details in a search for a generalising concept.” Sunlit Landscape (1924) consolidates hill, sky and orchard into interlocking colour plates, a pictorial grammar flexible enough to absorb both trauma and hope.

The new Soviet republic embraced him as proof that “national in form, socialist in content” could be more than a slogan. Party cadres praised his portraits of workers and intellectuals, yet what truly served the ideological project was his chromatic shorthand for Armenianness: apricot orange + indigo shadow = homeland. Under the policy of korenizatsiia (nativisation) such stylistic codes became state assets.

From the 1940s until his death, Saryan refined the formula into monumental canvases like Armenia (1964), where Ararat floats above a patchwork plain in colours so intense they seem back-lit. Here the mountain is less geology than emblem; hue supersedes line, suggesting that identity resides in spectral vibration rather than cartographic borders.

That spectral logic outlived him. Minas Avetisyan in the 1960s–70s, and countless poster artists after independence, recycled “Saryan orange” to signal continuity while shifting subject matter. Even today, a quick scan of Yerevan murals reveals his chromatic DNA flickering beneath street-art aerosol.

For AMCA, Saryan offers a template for thinking about art as soft infrastructure. His landscapes were never mere scenery; they were blueprints for psychological reconstruction after genocide, tools for Soviet nation-craft, and now—paradoxically—icons of a post-Soviet brand. Mapping that continuum helps us ask how colour, memory and statehood continue to co-author each other in contemporary Armenian practice.

We invite readers to explore our upcoming digital sliders that compare Saryan’s tempera studies with later oil panoramas, and to contribute family photographs or posters that show where his palette has migrated next. The chromatic nation he envisioned is still unfurling—stroke by stroke—in living rooms, studios and city streets worldwide. Join the conversation and add your own colours to the map.